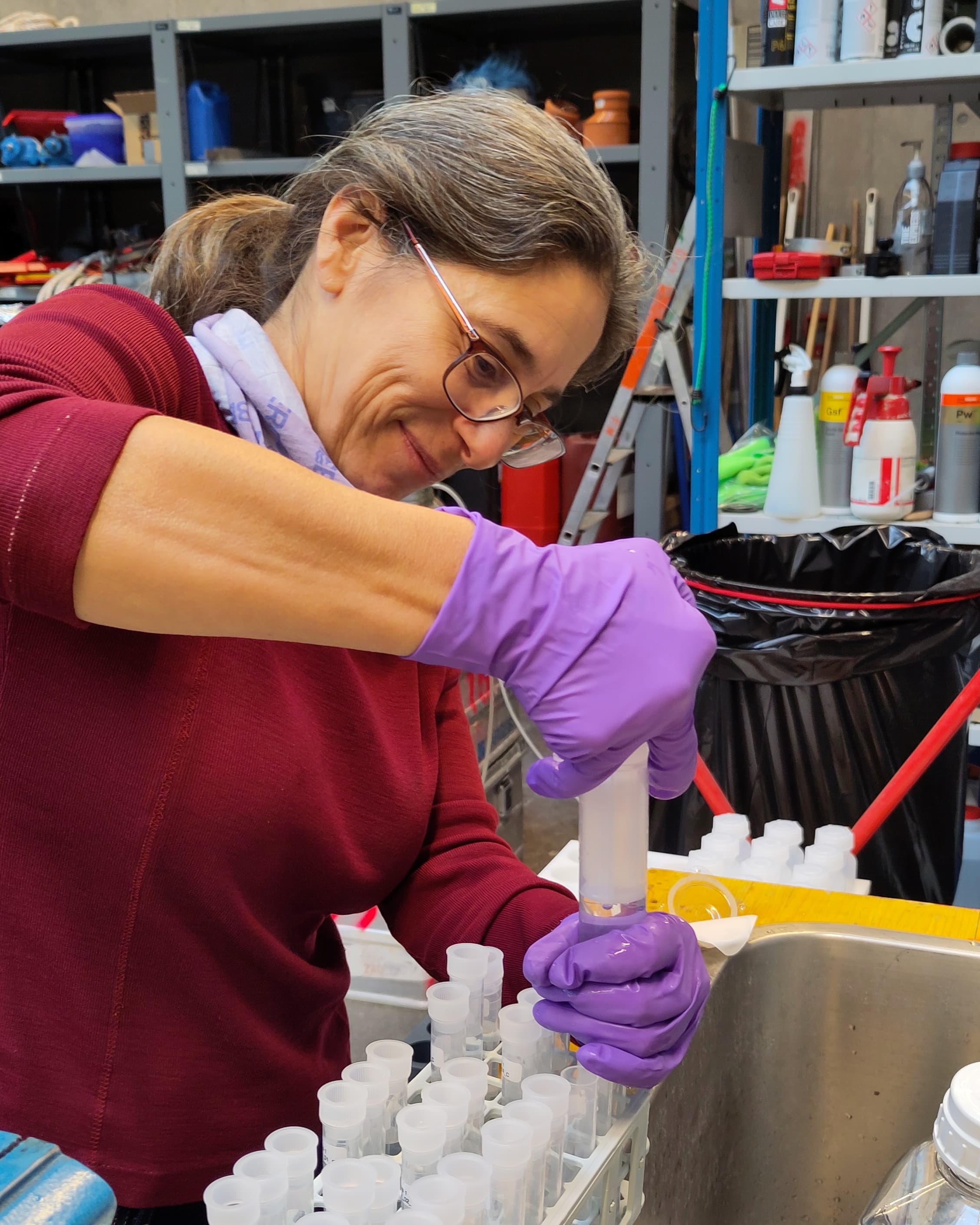

In addition, we sample for nutrients, organic matter, and different pollutant categories, such as metals and organic contaminants (e.g. PFAs, so-called forever chemicals). We compare the altered treatments to the control to understand if there is an influence of the pollutants.

Many of the samples need to be shipped back to Kiel or elsewhere for analysis, so we do not get the full set of results until a bit later. But we do see how our gases change right away, which gives us an idea about the effect of the pollutants. We are now in the middle of our first experiment – so there will be a few more days of work until we see the first results.

Saturday, 11 days after our arrival, is our first day off. We will use the day to sample wastewater streams from a cruise ship in the port, the MS Spitsbergen, then we will be sure to use the rest of the day wisely – hiking in the beautiful surroundings of Akureyri.

All in all, the beginning of our time here was a wonderful success – the people are friendly and helpful, the equipment works, the area is lovely, and the cold is not that bad. We look forward to the rest of our month here – and takk!

Text written by Christa Marandino and Dennis Booge (GEOMAR).

Main photo and photo of Akureyri town: Christa Marandino.