From Shore to Science—How Community Beach Clean-ups in Eyjafjörður Turn Litter into Research

Melanie Mobley from ICEBERG partner organization INRAE describes the atmosphere of beach clean-ups in Eyjafjörður, Akureyri, Iceland.

Melanie Mobley from ICEBERG partner organization INRAE describes the atmosphere of beach clean-ups in Eyjafjörður, Akureyri, Iceland.

Surrounded by snow-capped mountains, calm waters, and vast skies, Eyjafjörður, embracing the charming town of Akureyri in Iceland, seems pristine at first glance. However, as I quickly learned during my time here, even the most remote places are not spared from the global issue of marine litter.

During my week in Akureyri, I joined Anna Lauenburger and Isobel Stuart for the first beach clean-ups of the season in Eyjafjörður. Both are dedicated freelance coordinators for Ocean Missions and are leading this season’s efforts in the area. Their work brings together volunteers, many of them university students and internationals, eager to give back to nature and tackle the growing problem of ocean pollution.

Melanie Mobley (right) with Anna Lauenburger & Isobel Stuart who are coordinating Ocean Missions’ beach clean-ups in Akureyri this season.

At first sight, the beaches in Eyjafjörður don’t appear heavily polluted. But as we combed through the drift lines and rocky shores, it quickly became clear that litter was everywhere. Hidden among algae, driftwood, and stones were fishing buoys, nets, ropes, plastic canisters, and countless small plastic fragments carried by wind and waves. Some of this debris had clearly traveled far, arriving in Iceland’s northern fjord from distant corners of the ocean.

“It’s just nice to be able to go outside and engage in something that’s fun to do.” — Friðrik, volunteer from Iceland.

“It was fun, like doing it in a group. We were laughing all the time.” — Noelia, volunteer from Spain.

“I’ve always been interested in environmental issues – that’s a big part of my life. So that definitely motivated me. When I heard about the beach clean-ups, I thought, “Of course I care about that.” But honestly, a big motivation was also to get outside and meet people.” — Charlotte, volunteer from the United States.

One of the most inspiring aspects of the experience was the spirit of the people involved. Volunteers came not only to help but also to connect with nature and contribute to research. Some even brought their dogs along for the adventure. The energy was infectious; conversations flowed easily as we picked up debris together.

The support from local landowners also stood out. Many were grateful and encouraging, welcoming our presence and happy that someone was taking care of these often-forgotten spots.

A lighthearted moment came when volunteers began joking about who could find the weirdest or funniest piece of debris. Moments like this added a lot of joy to the task and kept spirits high.

And with good reason, almost every imaginable plastic item can be found on these shores.

From toothbrushes and dog toys to enormous pipes, shoes, toilet brushes, and even children’s toys, the variety of debris is astonishing.

Each clean up becomes a surprising treasure hunt, and spotting the oddest find of the day quickly turns into part of the fun.

During the clean-ups I participated in, about 30 people joined forces. Over the course of roughly five hours, we collected a significant amount of waste, 100 kg in total and more than 100 liters of polystyrene alone.

Anna, Isobel and I spent hours carefully separating and counting every item collected, ensuring that each piece was properly recorded, disposed of, or set aside for research.

“The counting can be difficult. The kind of trash we find is often very small or broken down, so it’s hard to identify.” — Isobel, organizer from the UK.

Yet despite these challenges, there was a sense of purpose throughout the process.

For many, the clean-up was about more than just filling bags. It was also a learning experience. Volunteers were curious about what would happen next, what role this collected waste would play in understanding marine pollution.

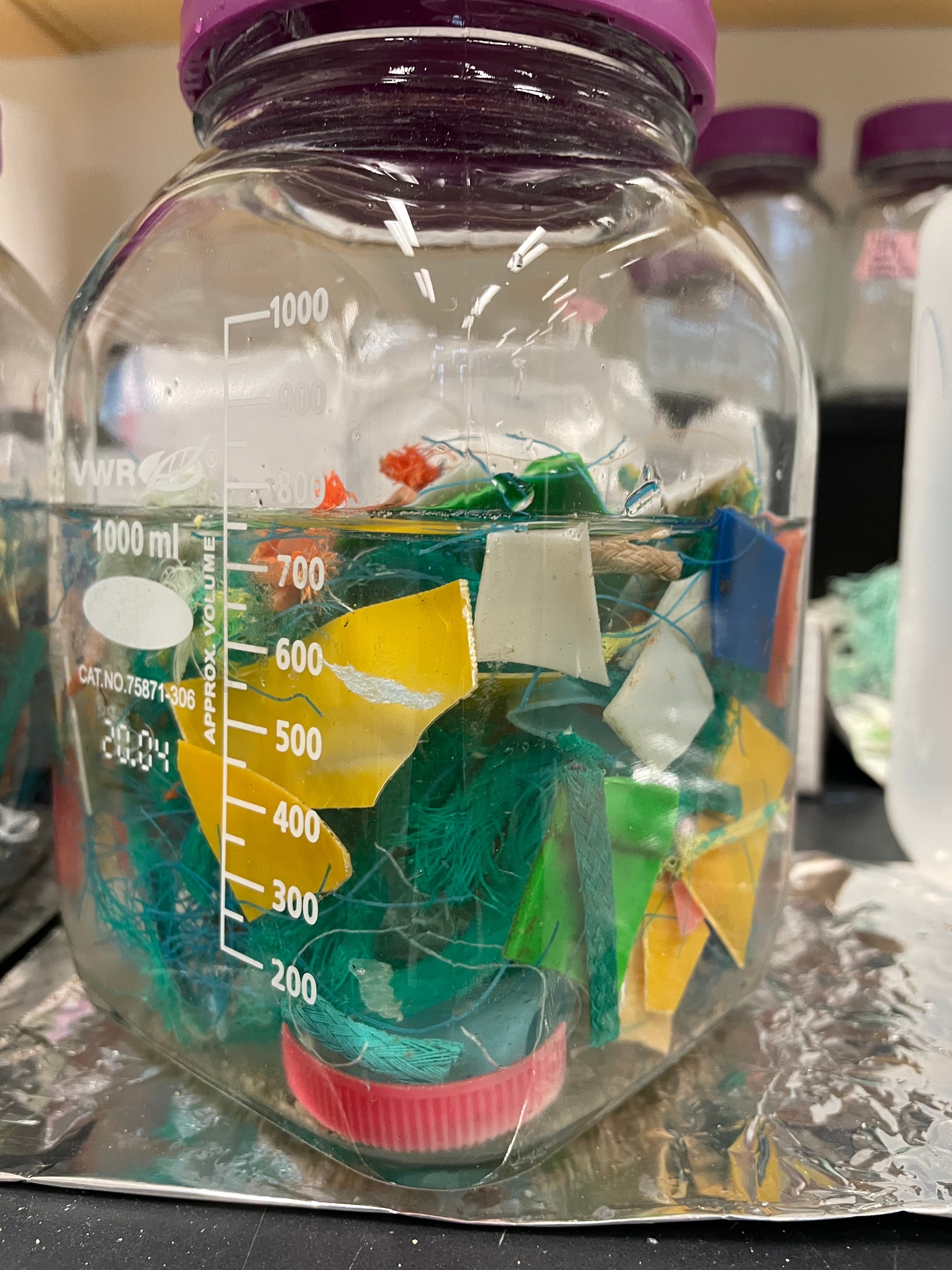

The plastic collected during the cleanups I was part of is used for ICEBERG’s research. We will process it in the lab to create environmental nanoplastics, tiny plastic particles (smaller than a thousandth of a millimeter) that are formed as larger plastics break down in nature.

These nanoplastics are especially important to study because they carry not only plastic material, but also chemical additives, manufacturing by-products, and pollutants absorbed from the environment. These particles are small enough to pass through biological barriers, including the human gut, and may affect human health.

Because this plastic has been exposed to Arctic conditions, sunlight, saltwater, freezing temperatures, it gives us a realistic model for how these nanoplastics behave inside the human body.

By simulating human digestion in the lab, we can explore how these particles interact with the gut and what potential risks they may pose to human digestive health.

Cleanups like these, therefore, are not just only about removing visible plastic but also help collecting samples that help researchers understand the long-term impacts of plastic pollution.

Learning about these challenges added a new layer of meaning to the day.

“Even small actions make a difference. People who join should know that what they’re doing matters. Every little bit helps.” — Isobel.

Participating in this clean-up made it clear that even in regions far from large population centers, marine litter finds its way onto beaches. It highlighted how interconnected this problem is and how vital local actions are in addressing a global issue.

What stayed with me most, though, was the dedication and positivity of everyone involved. The landscape was breathtaking, but so was the community spirit. Each piece of plastic collected, each muddy step, and each shared conversation felt like part of something bigger.

“Once you are aware of the situation, you can’t really unlearn that. Like, once you know what happens to a plastic bag, you won’t take one again, you’d rather carry your things by hand.” — Isobel

I left the week feeling inspired—by the landscape, by the dedication of the Ocean Missions team, and by the volunteers who gave their time and energy to make a difference.

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the scale of plastic pollution, but this experience showed me that community-led actions matter for the environment, for research, and for fostering awareness.

While we may not have been able to completely clean the beaches, each bag filled and every shared moment was a step forward.

Text written by Melanie Mobley (INRAE).

Photos by Melanie Mobley and Anna Lauenburger.

Want to know more about marine litter clean-ups? Be sure to read this previous blog text written by Barbara Jóźwiak (forScience Foundation).

Be also sure to subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media:

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the progress of the project.

SubscribeProf. Thora Herrmann

University of Oulu

thora.herrmann@oulu.fi

Dr Élise Lépy

University of Oulu

elise.lepy@oulu.fi

Marika Ahonen

Kaskas

marika.ahonen@kaskas.fi

Innovative Community Engagement for Building Effective Resilience and Arctic Ocean Pollution-control Governance in the Context of Climate Change

ICEBERG has received funding from the European Union's Horizon Europe Research and innovation funding programme under grant agreement No 101135130