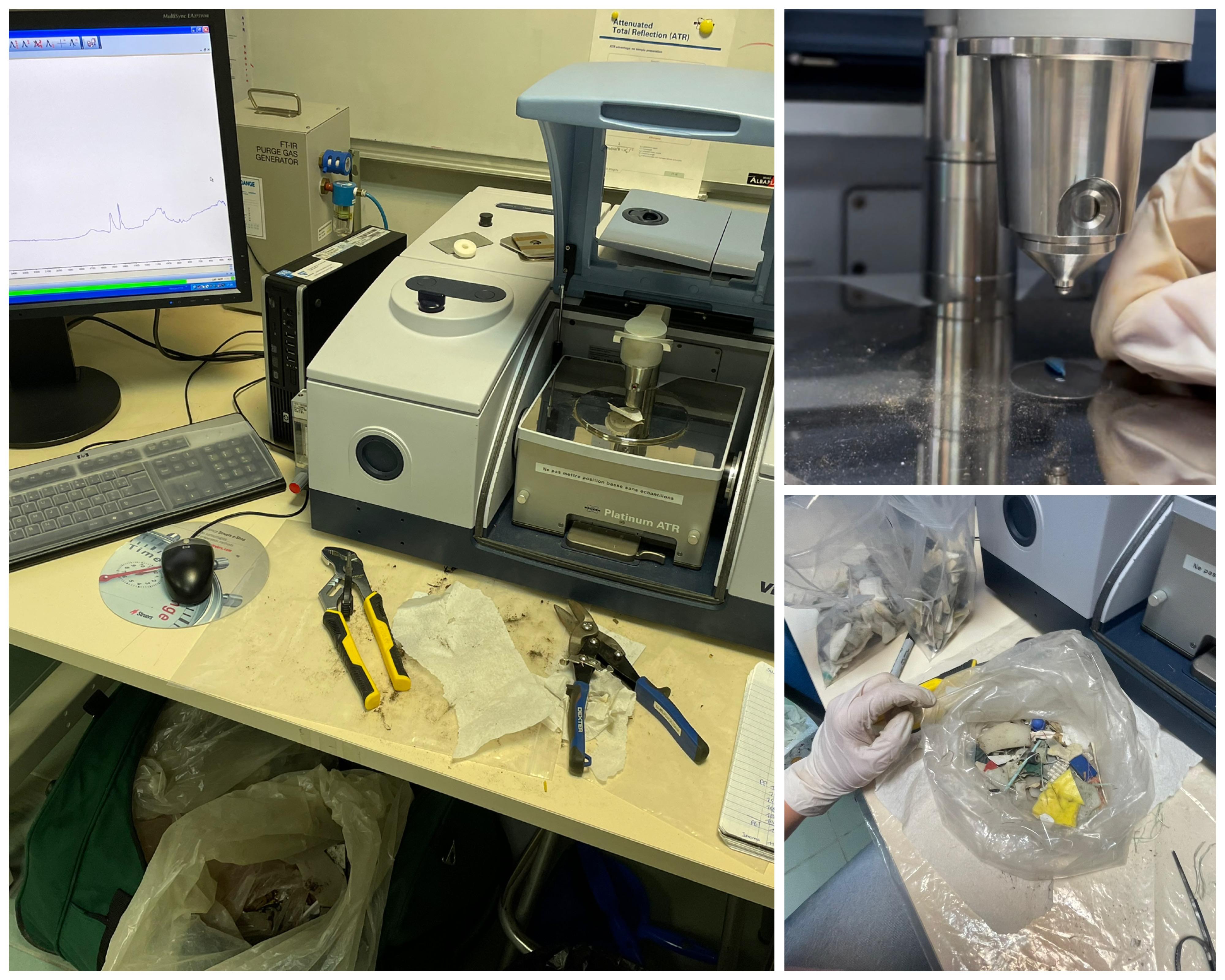

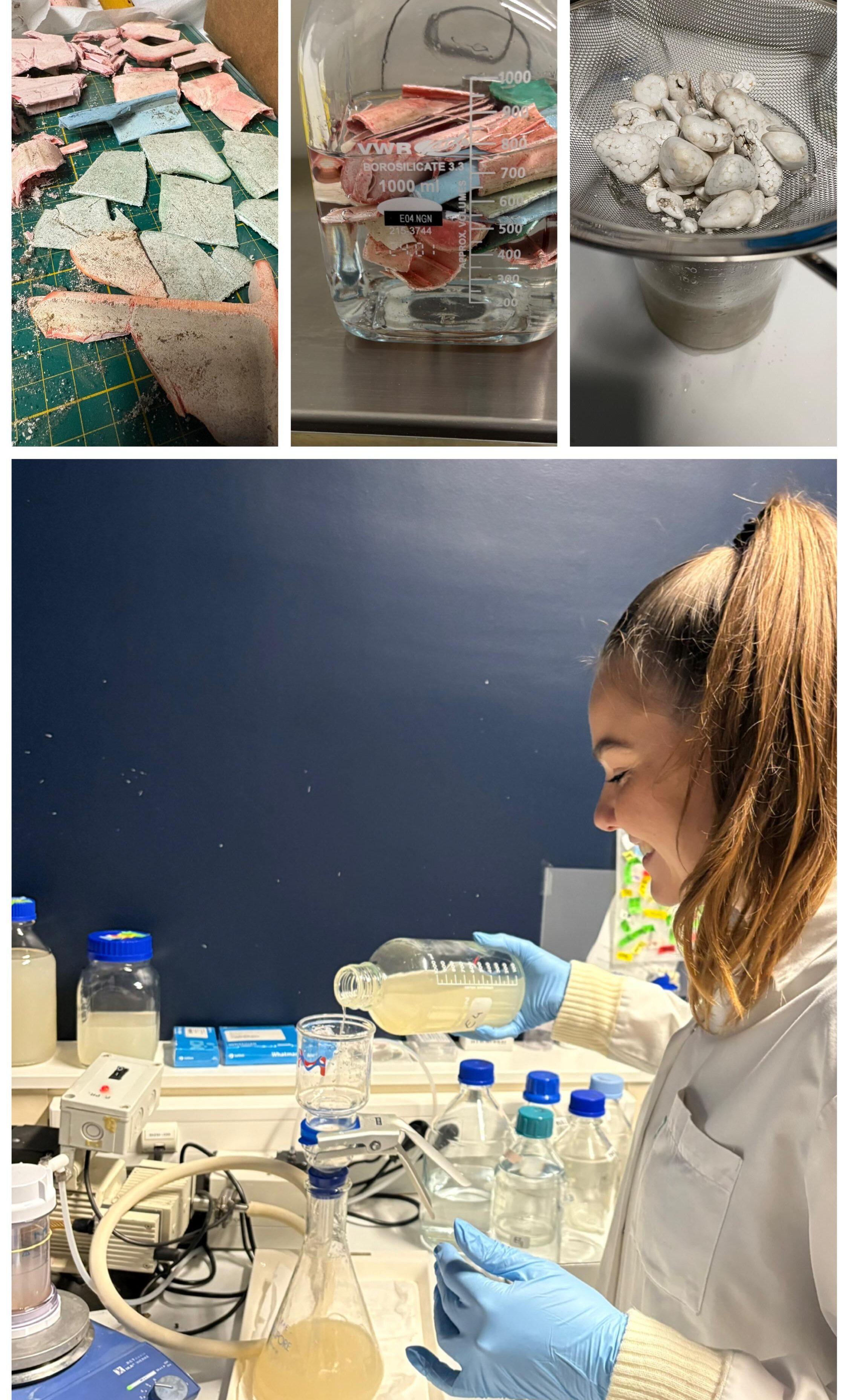

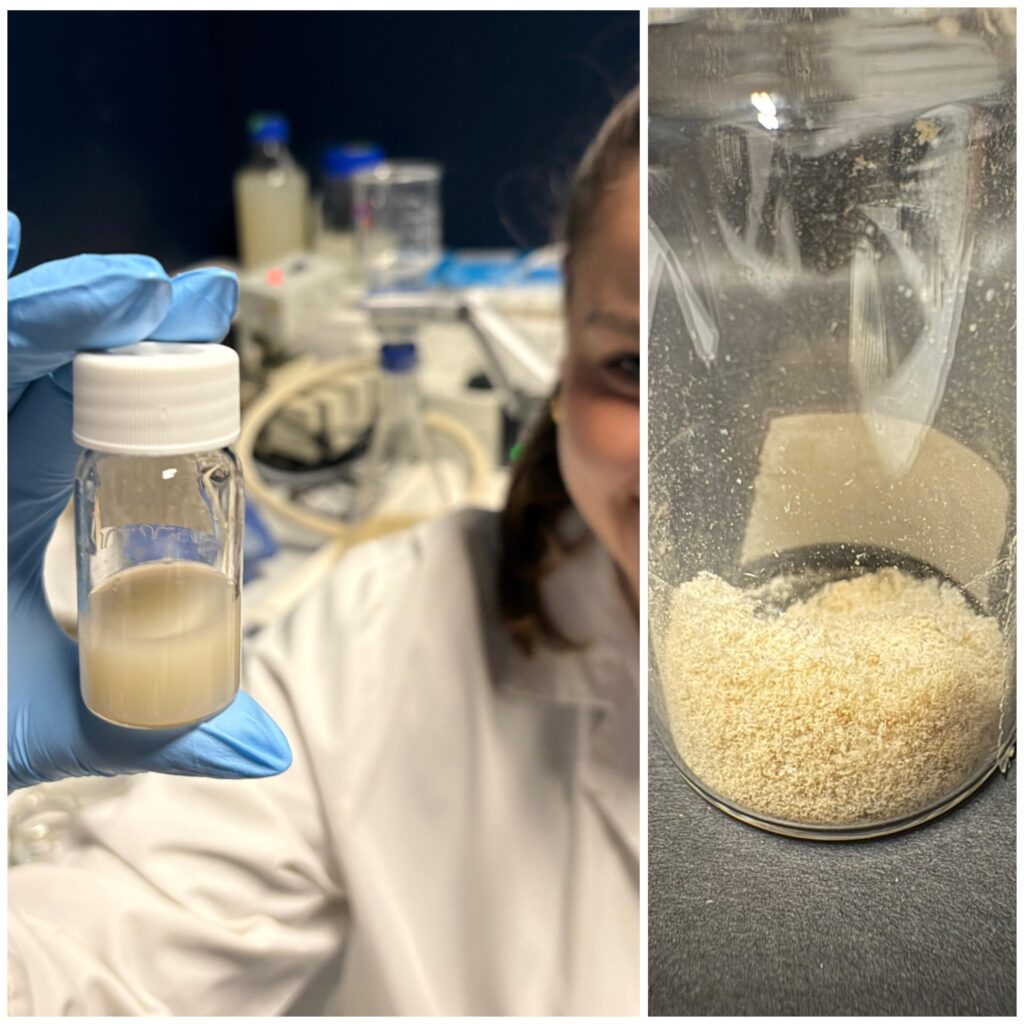

This approach also highlights the complexity of marine plastics. They are not simply clean polymers, but materials that have aged and interacted with their surroundings. They carry additives, absorbed contaminants, and biological residues, all of which can influence their behaviour and toxicity. Understanding this complexity is essential to grasp the true impact of plastic pollution. Using real beach plastics rather than pristine, factory-made polymers provides a far more representative picture of what is occurring in nature.

The main challenge with this method, however, lies in producing sufficient quantities of nanoplastics for biological testing across different criteria. Despite this, the insights gained from such environmentally relevant materials are invaluable for assessing real-world impacts on health and ecosystems.

Plastic Pollution on a Global Scale

The urgency of this work resonates beyond the laboratory. The United Nations and its Environment Programme recognise that we are facing a Triple Planetary Crisis, with irrefutable evidence for the impacts of human activities on the planet. We face the unprecedented threats of anthropogenic climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution driven by unsustainable production and consumption of energy, chemicals, materials, products, and technologies. As stated by the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty, plastics and associated chemicals are at the centre of this crisis.